|

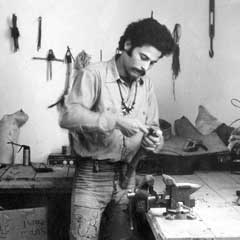

Vaadia, who used stones as a child on an Isreali farm to make pieces that imitated the art he saw on weekly visits to the galleries and museums of Tel-Aviv, rediscovered their mieaning to him in his early twenties after years of art-school and private experimentation with every other kind if sculpture material. Finding stone again was nothing less than a revelation to him. He remembered that he'd asked for an African fetish as his 13th birthday present, because he'd been so impressed with the primitive sculptures he'd seen in the museums. In 1972, after his first one-man show of painted metal sculptures, he realized that certain materials threw otherwise well-designed pieces out of balance and that he wanted to shape works naturally, so that the laws of gravity, counter-balance and tension dictated the forms. Preconceived shapes and formal but not physical problem-solving had come to seem as artificial as synthetic materials The initial pieces Vaadia made with natural materials — stone, fur, hair, leather, wood and bronze — bore a superficial resemblance to Surrealism, but were actually precociously Neo-primitive, particularly for an artist working so physically far from the center of the avant-garde. Many of his pieces from the past five years continue to have the fetishistic quality of those late Isreal-period works, and they continue to contrast hard and soft materials within a given piece, but they are less organic or biomorphic and more geometrical. The pieces done in Manhattan not only reflect the rectilinear architecture that forests the island, and the many bridges that arch off its shores, but are also actually constructed of stones and timber found in the area. Since 1977 Vaadia has been wrking with slabs or blocks of stone either supported by, or bound into wooden frameworks of slender cedar logs lashed together with leather thongs. These logs are the same as those used to support young trees in our sidewalk oases, and the slabs of stone are sills, ledges, and curbstones recycled out of the city's continual de-construction. Like the Philosopher's Stone, which is familiar to all yet unprized except by the wise who know of its gold within, his stones are the cast-offs of urban decay transformed into works of art. The city streets are a sculptor's supply paradise, as Vaadia discoverd soon after his arrival here in 1975: with a van, a lever, a skid on wheels and an occasional hellping-hand, you can garner all the bluestone, granite, brownstone and slate you can use. Vaadia loves the way these stones are layered in sheets that can be lifted-off deftly aimed chisel blows; he also loves the "peels" of quarried rock, those top layers which evince the ravages of weather over time. Working into the stone from all six sides, he shapes it in sympathy with its natural lines and characteristics. The resultant look is like stone-chipped arrowheads rather than metal tool-carved sculpture, and has a raw, primitive urgency about its apparent lack of finish.

Vaadia's major installation at the Jewish Museum in 1978, his wall pieces, and some of his models for large swing or bridge-like pieces operate on an opposite principle. Here the stone's wieght is pulling away from the support, which must be in turn secured by wall or base attatchments, and one reacts to this tension situation somatically, with some trepidation. In an arch these two opposed directional thrusts are fused (suspension bridges are based on a fusion of arches and counter- thrusts too) and Vaadia has long planned to execute a major outdoor "keystone" arch piece. The massive construction of an inverted arch in 1981 represents a variation on this theme; it resembles a suspended rope bridge, in fact. A number of 1977-79 pieces were rectangular cages of wood surrounding or supporting upright slabs of stone. This image — it conjures up Oriental fenced-in magic rocks, Andean monoliths, and protected steles of Greek or Mayan sites — is continued in recent works where two slabs are now enclosed by the ceder posts, but it also connects in meaning (though not morphologically) to a group of less typical works he's done during these five years. At Bear Mountain the wood frame seems to hold up the mass of stone it encloses (though it couldn't), and in the group of cobble stone dolmens he erected at Ward's Island in 1979 there is a similar sense of the atrist's intention to recall primitive, ritual- associated, uses of stone. Interestingly, the one piece he's done between 1977 and now which is organically rounded instead of rectilinear or made of cubic shapes, was executed in Isreal where the pull of the land and its associations for him with earlier primitivizing and biomorphic work is very strong. Smaller stones "spill out" of large ones in three groupings which look like conjunctions of the monolith and the stcked dolmen. If Vaadia had done that pieces in certain places in Melanesio where people believe that sacred stones have miraculous powers corresponding in kind to the stone's shape, he might have been rewarded with riches or an increase in his own crops, or his livestock's fertility because the units resemble bags with spilled-out seeds or coins and, less distinctly, a sow among her litter. Such possibilities are not completely foreign to Vaadia's deepest convictions about the spiritual potential of the simple stone. © 1981 April Kingsley

|

In the Chinese garden, a well-eroded stone stands-in for the mountain home of The Immortals.

The stone's owner hopes to learn the secret of immortality when The Immortals come to visit his

surrogate rock formation. In the pre-Columbian Andes, stones that resembled human forms were

worshipped, and in Christian times people carved stone "likenesses" of God for the same purpose.

Various primitive peoples use stones to produce rain, or conversely, sunshine, and in more than

one tribe stones function as external souls. Our own Pet-Rock craze of a few years ago was

distantly, bun dinstinctly linked to this universal sense of "stone power." In contemporary

sculpture by artists as disparate as Rodin, Brancusi and Noguchi, one senses a shared concern

and respect for the spiritual potential of the stone itself. For Boaz Vaadia, using stone is

like making sculpture out of the bones of the earth.

In the Chinese garden, a well-eroded stone stands-in for the mountain home of The Immortals.

The stone's owner hopes to learn the secret of immortality when The Immortals come to visit his

surrogate rock formation. In the pre-Columbian Andes, stones that resembled human forms were

worshipped, and in Christian times people carved stone "likenesses" of God for the same purpose.

Various primitive peoples use stones to produce rain, or conversely, sunshine, and in more than

one tribe stones function as external souls. Our own Pet-Rock craze of a few years ago was

distantly, bun dinstinctly linked to this universal sense of "stone power." In contemporary

sculpture by artists as disparate as Rodin, Brancusi and Noguchi, one senses a shared concern

and respect for the spiritual potential of the stone itself. For Boaz Vaadia, using stone is

like making sculpture out of the bones of the earth.